Journey of a special needs student: Part 1

November 13, 2018

As students begin high school, new accommodations are available to individuals with disabilities. The most common are the Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and 504 Plan, and there are many details and options entailed in each.

An IEP is for children who qualify for special education services. The child must have a documented learning disability, developmental delay, or speech impairment. Special education services are offered in an individualized learning format. On the other hand, a 504 Plan involves classroom accommodations, such as behavioral modification and environmental support.

To apply for an IEP, parents can ask to have their child evaluated by the school for free. After evaluation, students must have one of the 13 disabilities listed under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). However, having one of the 13 disabilities under IDEA does not automatically qualify a child for an IEP. There also needs to be proof that as a result of the disability, the student cannot succeed in school.

If a student is denied an IEP, then they can apply for a 504, which does not offer individualized instruction, but provides changes to the environment, instruction, and how curriculum is presented. A 504 only alters how the student learns material, not what they are learning. The application process for a 504 is simpler than an IEP. Parents can request one to the school, then schools will look at the student’s grades, medical diagnosis, or teacher recommendations.

On Oct. 17, a panel of nine representatives spoke at the Special Needs Speaker Series at Gale Ranch Middle School about programs available to individuals with disabilities during and after high school.

“Our community wants to show all the ways [students and parents] can find help and support,” said Christine Koehne, the SRVUSD special needs liaison. “We want our students to become their best advocate, thinking for themselves.”

The most accessible program to SRVUSD students is WorkAbility, a transition program affiliated with the district. For students who are 14 to 22 with an IEP, they can get one-on-one aide from coordinators in their classrooms. The SRVUSD coordinators, Susan Frankel and Noralyn Giles, believe that participating in outside services is essential for all high school students with disabilities.

“We contact all our students one year after high school [and] hear over and over how difficult it is to transition without signing up for a disability service,” Frankel said. “It really is necessary. Last year, we started signing students up for DSS [Disability Support Services] in the classroom.”

WorkAbility’s goal is to teach life skills to those in special education. The program offers post-secondary education, employment training, and independent living.

“Our big focus is getting job experience,” Frankel said. “What we find with our students is that everyone is afraid of that first job, but once [they are] able to say that they’ve worked and succeeded, it’s truly a life-changer with the confidence and self-esteem it builds.”

After high school, all IEPs convert to a 504. For many students, adapting to a more independent lifestyle can often be challenging in addition to more limitations.

“Higher education often sucks,” said Carolyn Warren, a Diablo Valley College counselor. “Students with disabilities are often the last to be considered when it comes to changes. We are constantly questioning the system.”

Educators encourage students to begin practicing advocating for themselves before college because there is less support as they progress in school.

“Instructors can be ignorant,” Warren said. “Every so often, I have a student who tells me that the teacher blatantly announces for them to go to another room. We always encourage them to talk to the Department Chair. We’re helping them build the skills of self-advocacy.”

By enrolling in Disability Support Services (DSS) at DVC, the community college supports anyone with a diagnosed disability to have access to personal accommodations.

“We try to match services to students’ specific needs,” Warren said. “All students [with DSS] will get extra time on testing and note-taking services.

We can add accommodations based on what the student is telling us.”

Although services are provided, there are no longer one-on-one aides alongside students, so they often need to become more independent and seek help when they feel it is needed.

“Funding becomes less once they go to college, so we just want to prepare [students and parents] for that,” Warren said. “There is less flexibility in college and more limitations which lends less compromises. A lot of support students’ needs come from our tutoring services.”

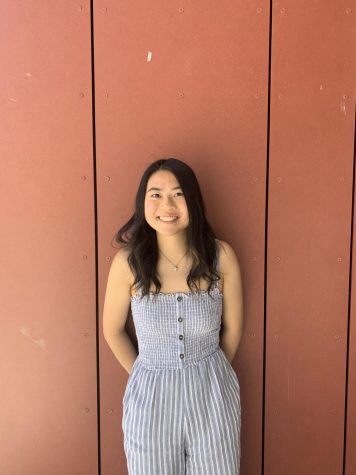

Gabrielle Pangilinan, a second-year student and student ambassador at DVC, has bipolar disorder and is studying psychology to continue exploring the field. She has found success in DSS despite the barriers she has had to overcome.

“I really had to learn how to be comfortable with telling my teachers and boss that I needed help, so they would be prepared if I had panic attacks at school or work,” Pangilinan said. “It really helped me to be in Disability Support Services because it helped me figure out what I wanted to do with my major. I was undecided at first, but I started becoming interested in my own disorder and how I could help people like me.”

Many students in DSS transfer to a university after two to four years at DVC. It takes motivation to get to that point, but faculty strive for the interests of their students.

“If a student is working hard in academics, it is very likely to get into a university,” Warren said. “Most students just need to know they can do it, and the foundation of DSS is counseling. If students don’t seek help, then we can’t help them.”